When Charles Ponzi was arrested 105 years ago he had just raised as much as $20mn in seven months. Thousands of Americans had fallen for his scam investment scheme that promised to double their money in 90 days.

Depending on whether you are a signed-up crypto bro or not, bitcoin is either a brilliant innovation to move the world away from corruptible fiat currencies or a vast confidence trick. The advent of bitcoin treasury companies that raise debt and equity merely to buy bitcoin is, by extension, either genius financial engineering, or something akin to a Ponzi scheme upon a Ponzi scheme.

Such shorthand may be clumsy — crypto does not explicitly rely on new investors to remunerate existing ones as Ponzi did; and fraud, though sometimes connected with crypto, is not inherent to it. But there are still alarming similarities, most obviously the mood of cultish exuberance. Over the past year, bitcoin is up more than 80 per cent, four times the gain of the trendily tech-heavy Nasdaq index; who knows — it might manage 100 per cent in 90 days at some point.

Now consider a more recent parallel. Collateralised debt obligations — the mortgage derivatives that boomed in the years up to 2008 — were, again like crypto, a hyped asset class with little fundamental value (thanks to the ropey underlying loans that mortgage brokers were originating to meet feverish CDO demand).

As the fever peaked, CDOs were so hot that financial engineers dreamt up the CDO-squared — made from an amalgam of other sliced-and-diced CDOs, which in turn had sliced and diced the original ropey mortgages. Disaster, predictably, ensued.

Bitcoin treasury companies are in a sense the CDO-squareds of the crypto universe. If you thought bitcoin mania was over the top, how much more so is the BTC — a company that either in part or entirely puts its cash into bitcoin or other crypto coins.

These are groups that were previously struggling tech designers, marketing companies or education consultancies, have thrown in the day job and punted on bitcoin. There are now dozens of them.

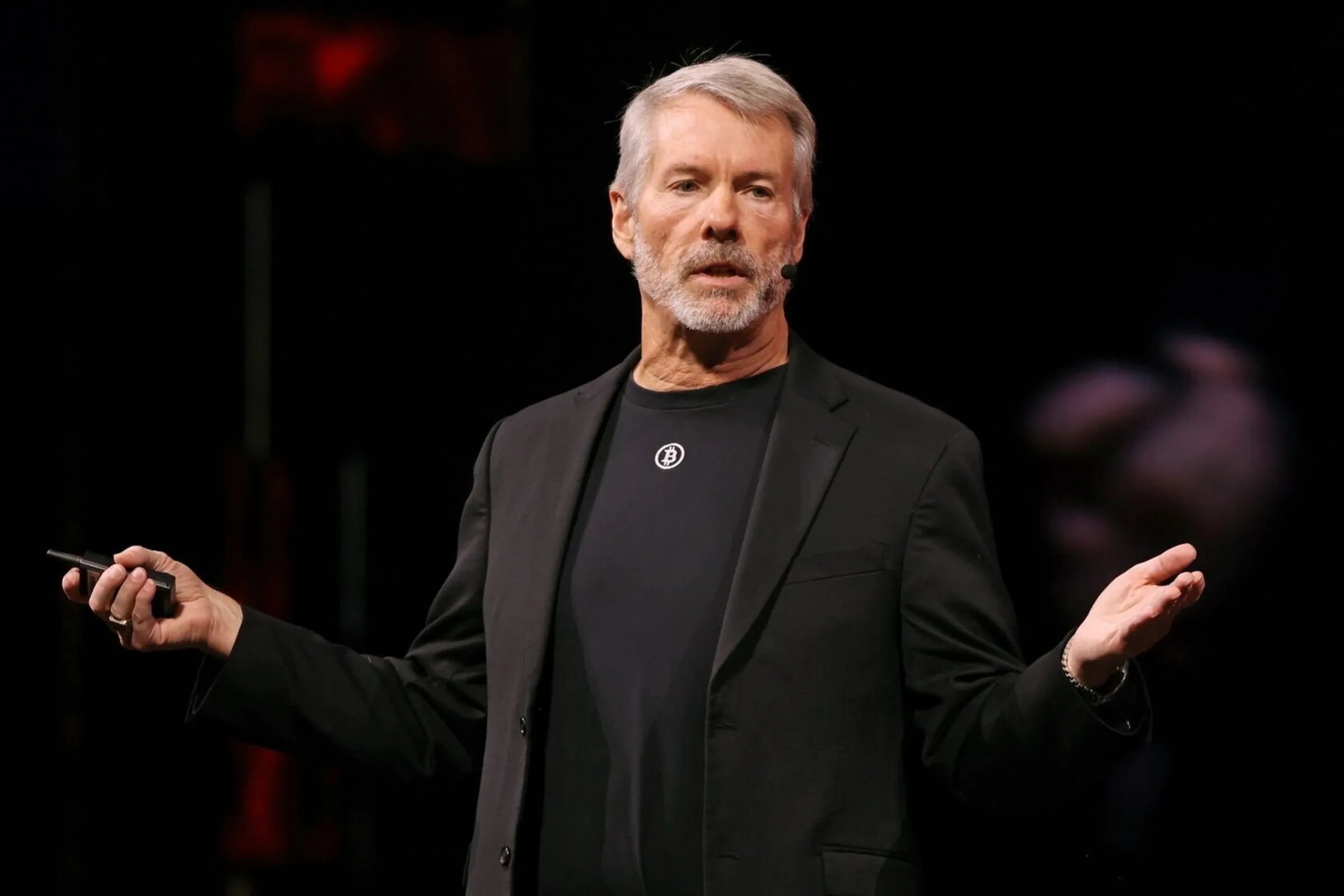

According to brokerage firm Peel Hunt, there are now more than 160 BTCs globally. All have been inspired by the story of Michael Saylor, who did just this with his software company Strategy (formerly MicroStrategy), and has been rewarded with more than 20-fold growth in the company’s share price since 2020. Strategy’s market capitalisation is now well over $100bn, triple the value of State Street.

In the iconoclastic world of bitcoin and BTCs, the concept of safeguarding company funds by a corporate treasurer in low-risk instruments goes out of the window — and into bitcoin. And more than that, the company then raises fresh equity, or issues a stream of debt or convertible bonds to expand those crypto holdings. Peel Hunt describes this as a “flywheel”.

For investors, the main appeal seems to be that they can plug into the upward momentum of crypto valuations, with built-in leverage.

In addition, there are multiple layers of arbitrage. First, depending on your location, there may be a tax play. In some jurisdictions, such as Japan, a corporate structure like a BTC would attract a lower rate of capital gains tax than a direct investment in crypto. In others, BTCs could be sheltered from tax altogether via tax-free stocks-and-shares wrappers.

Regulatory arbitrage may also be a draw. Crypto ETFs, for example, have yet not been authorised in the UK for retail investors; a BTC skirts that restriction. And for institutional investors, a corporate structure may circumvent a mandate that blocks them from holding crypto or other alternative assets directly.

In a relentlessly rising market, dodging roadblocks such as this, and maximising returns through leveraged BTCs, may feel smart. The market’s exuberance has certainly been boosted by Donald Trump’s government, particularly via his recent executive order to pave the way for 401(k) pensions to buy crypto, and his “Genius Act”, which will boost digital assets more broadly. (The Trump family’s own media company has itself pursued a $2bn bitcoin treasury strategy.)

As long as the bull run continues, BTCs — not very different from a Ponzi scheme upon a Ponzi scheme or a CDO-squared — may prosper. But “crypto winters”, as the “bros” discovered in 2018 and 2022, tend to be harsh; come the next one, BTC investors are likely to find the misery is squared, too.