In the early 1970s Princeton University astrophysicist Jeremiah Ostriker was puzzling over telescope observations of distant galaxies. These spinning cosmic discs did not contain nearly enough stars and other visible material for gravity to hold them together. The answer, he realised, must be that a much larger mass of unobserved “dark matter” stopped them flying apart.

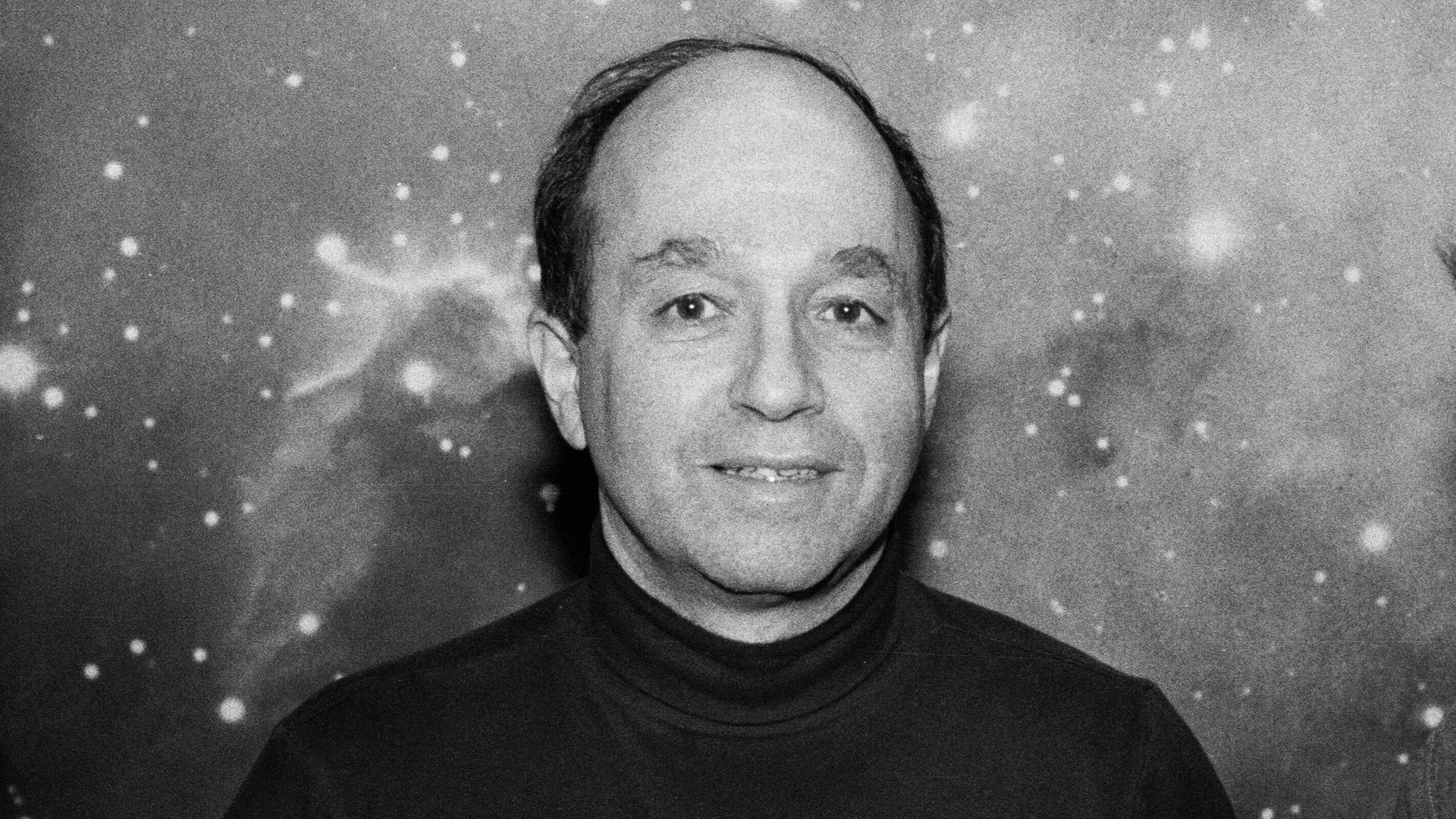

Though there had been scientific speculation about dark matter since the 1930s, Ostriker, who has died at the age of 87, played an instrumental role in convincing cosmologists that it really did pervade the universe. The consensus today is that dark matter has a total cosmic mass six times that of ordinary matter — close to the proportion calculated by Ostriker and his Princeton research group in a key 1974 paper. But astrophysicists still have little idea of what makes up dark matter.

With his wide-ranging and deeply inquiring mind, Ostriker worked productively on a remarkable range of problems across astrophysics, says Martin Rees of Cambridge university, Britain’s Astronomer-Royal, who knew him as a friend and colleague: “He was interested in all the new topics that came up and which later became part of the scientific consensus.”

Among other achievements, Ostriker contributed significantly to advances in understanding how pulsars emit radiation, the vast volumes of space between stars, the role of cosmic gas clouds in galaxy formation and the dynamics of supernovas.

Jerry Ostriker, as he was generally known, was born in April 1937 into a Jewish family in New York. His mother taught in a public school and his father owned a clothing company. In boyhood he was obsessed with science, even taking the subway down to a Broadway bookstore to buy Teach Yourself Calculus aged 13.

At Harvard University Ostriker took a degree in science but found classes in art, history and literature more stimulating. “I remember thinking that the course I took from the poet Archibald MacLeish was the best training for science that I took at Harvard,” he wrote in a 2016 memoir. His greatest personal achievement at university was marrying Alicia Suskin, an undergraduate at nearby Brandeis University who became an award-winning poet as Alicia Ostriker.

In contrast, he recalled, the Harvard astronomy course was “so bad . . . that I had to petition the dean’s office to drop it after one term”. But Ostriker was not put off astronomy as a subject and he went on to do a PhD and postdoctoral research in astrophysics. In 1965 he became a lecturer at Princeton, which remained his main academic base for the rest of his life, though he spent time at other universities, including a professorship at Cambridge.

Unlike many academics, Ostriker was happy to devote time and energy to administration, working for long periods as departmental chair and then provost at Princeton.

His key administrative contribution to astronomy was as a scientific leader and fundraiser for the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Operating since 1998 from a dedicated telescope in New Mexico, this has provided the most comprehensive map of the visible universe. Ostriker insisted that data from the survey should be freely available to astronomers worldwide, which has resulted in 10,700 research papers, including a wide range of discoveries.

As university provost, Ostriker pioneered initiatives in financial aid “which have succeeded . . . in making Princeton significantly more attractive to a much more diverse group of students,” his academic colleagues wrote in a testimonial.

Ostriker emphasised his personal commitment to promoting diversity in his 2016 memoir. When women were able to enter astronomy as full-fledged colleagues in the 1960s and 1970s, he wrote, “the original achievements were immediate and enormous”.

So it was a proud moment in 2012, the year he became professor emeritus at Princeton, when the university appointed his daughter Eve as professor of astrophysics. “Growing up, I don’t think either my father or myself had the expectation that I would go into the ‘family business’,” she says.

“What ended up attracting me to astrophysics in graduate school was, I later learned, the same thing that had attracted him 30 years earlier: the fact that the universe presents us with problems that can — at least in principle — be solved,” she says. “What he most enjoyed was to learn about a puzzling new phenomenon, to come up with an array of ideas for what might explain it and then to work through each one.”