Many one-product companies run out of road. Small plastic bricks have supported Denmark’s Lego for more than 70 years. A clear focus can pay off. But, amid a debate over the health of public markets, its success also demonstrates the benefits of its distinctive corporate structure.

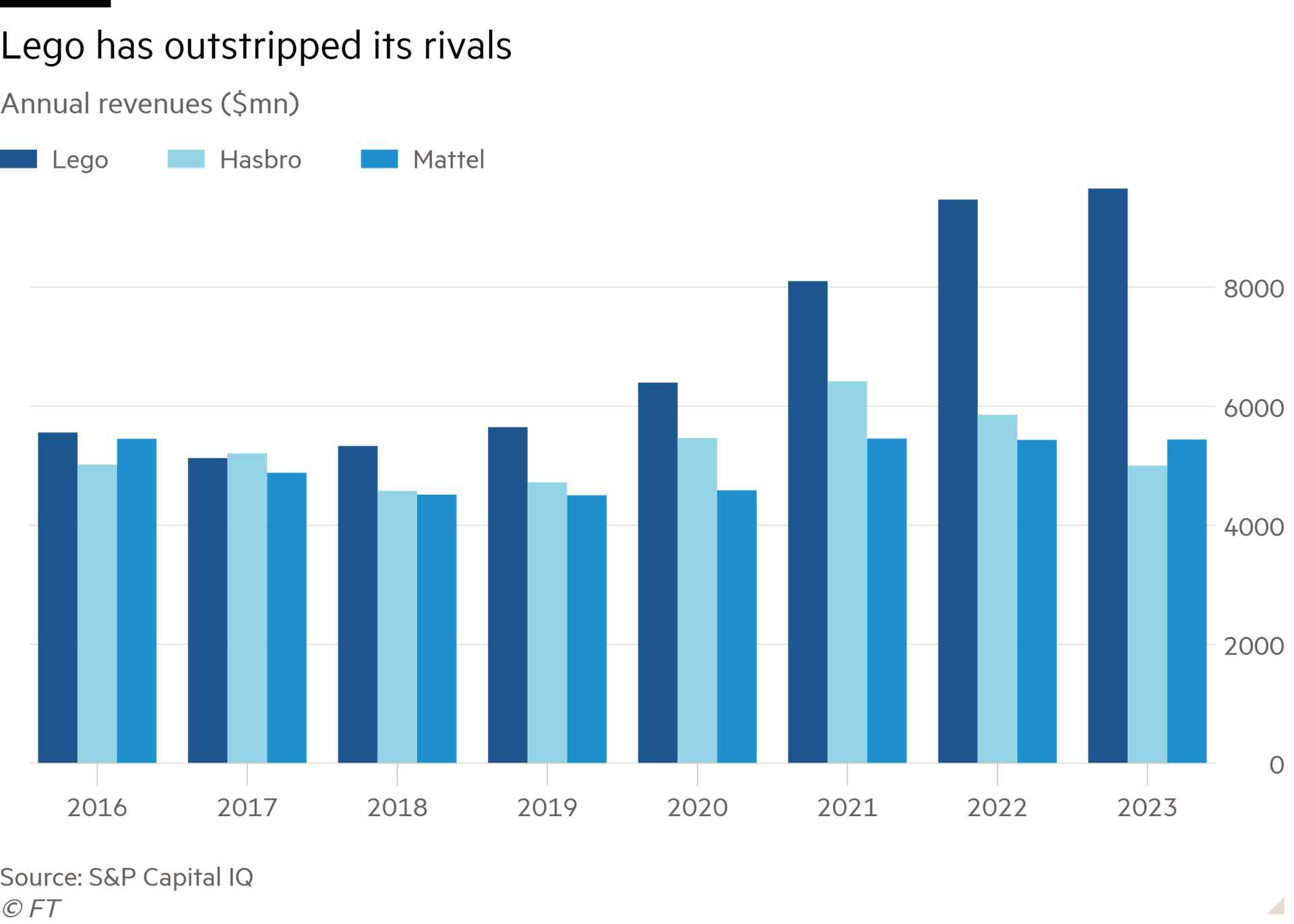

The toymaker’s sales growth of 2 per cent last year was dragged down by a weak performance in China. But it was respectable enough given a seven per cent decline in toy industry sales. Lego’s sales are not much less than the combined total of its quoted US rivals Mattel and Hasbro.

Inflation, one cause of the industry’s woes, is subsiding. Low birth rates, another problem, will persist. That is partly offset by adult fans of Lego. This group — known as Afols — creates a market for costly, complicated kits like the Titanic or Eiffel Tower. This “Icons” line made some of the biggest gains of any toy property globally in 2023, according to Circana.

New products accounted for roughly half of Lego’s portfolio last year. Innovation isn’t without risk: novelty can damage profitability if it means fewer universal pieces that can be produced in high volumes for lots of different kits. The proliferation of parts contributed to Lego’s downturn in 2003, says academic David Robertson. However, the business has since expanded so it can use more parts without hurting the ratio of sales to profits.

Lego’s operating profit margin fell by 1.7 per cent to 26 per cent, as it spent more on stores, its supply chain and digital operations. Even so, that is nearly three times Hasbro’s adjusted operating figure. Were it quoted, Lego would be worth much more than the $43bn estimate arrived at by using Hasbro’s trailing EV-to-ebitda ratio of 15.5 times.

But Lego is privately held and there is no sign of that changing. Kirkbi, an investment vehicle run by the founding family, owns 75 per cent, with the remainder owned by the Lego Foundation. When an heir opted to sell some Kirkbi shares for $930mn last year, family members took up the slack. Outside investors’ only exposure to the brand is through Legoland-owner Merlin Entertainments. Blackstone and Canadian pension fund CPPIB teamed up with Kirkbi on the £6bn take-private bid in 2019.

External investors might have been less inclined to tolerate last year’s 10 per cent dividend cut to fund investment. There is evidence that tightly held companies like Lego benefit from a long-term perspective. Building the business, like its product, is an exercise in patience. It can yield impressive results.